Managing hemophilia A in an evolving treatment landscape: payer considerations

Introduction

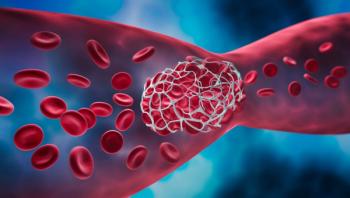

Hemophilia A is an X-linked recessive bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency of clotting factor VIII (FVIII).1 Because hemophilia-related bleeding can lead to musculoskeletal damage and other complications, the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) sets a clinical target of zero bleeds for people with hemophilia A (PwHA) and recommends prophylaxis over episodic (“on demand”) therapy for all patients.2

Intravenous prophylaxis with plasma-derived or recombinant clotting factor concentrates (CFCs) constitutes regular replacement therapy for PwHA.2,3 Nonfactor replacement therapies offer alternative mechanisms of action and modes of administration.2

For those who develop antibodies (inhibitors) to CFCs, prophylaxis with the clotting-factor mimetic emicizumab is recommended.2,3 This article reviews clinical and economic impacts of hemophilia A, guideline recommendations for management, and payer considerations, with a focus on CFC- and emicizumab-based prophylaxis.

Management of hemophilia A

Hemophilia A is managed prophylactically, episodically, and perioperatively. Although episodic therapy reduces the impact of individual bleeds, it cannot change the natural history of the disease, prevent future bleeds, or eliminate bleeding-related complications. The WFH recommends against episodic or reactive care and endorses prophylaxis. Prophylaxis with hemostatic agents can prevent bleeding, avert related complications, and enable PwHA to experience improved quality of life.2

Guideline-recommended therapies

The WFH and NHF recommend that patients with hemophilia A receive prophylaxis with FVIII or nonfactor replacement therapies (Table).2-4 About 30% of patients with severe hemophilia A will develop inhibitors.5 For patients who develop inhibitors, the WFH and NHF recommend treatment with emicizumab.2,3 Although nonfactor bypassing agents (activated prothrombin complex concentrate, recombinant activated factor VII concentrates) can be considered in some cases for these patients, the NHF notes that treatment with these agents is less effective than is treatment with emicizumab.3,4

For patients treated with emicizumab who experience acute or “breakthrough” bleeding, treatment with FVIII agents is recommended; for those patients with inhibitors, bypassing agents should be used.2

Clinical impact

Although hemophilia A can cause fatal hemorrhage after surgery or trauma, bleeding into joint tissue is more common. Untreated bleeding can lead to pain, joint damage, severe limitation of motion, and permanent disability. Patients with severe disease as well as those in whom disease is not adequately managed are most at risk.6,7

For PwHA, disease severity and clotting factor deficiency are typically correlated. Severe disease, which occurs in up to 70% of PwHA and is characterized by spontaneous bleeding, corresponds with FVIII levels of less than 1 IU/dL plasma. Moderate disease, defined by occasional spontaneous bleeding and extended bleeding after surgery or minor trauma, is associated with factor levels of 1 IU/dL to 5 IU/dL. Factor levels of 5 IU/dL to 40 IU/dL correlate with mild disease, which is associated with rare spontaneous bleeding and with severe bleeding after surgery or substantial trauma.2,8,9

For all PwHA, spontaneous bleeding is uncommon when baseline FVIII levels are above 15 IU/dL. However, the rate of spontaneous bleeding increases as patients on prophylaxis spend more time with FVIII levels below 1 IU/dL.2

Episodic treatment of bleeding has been associated with lower quality of life and higher morbidity when compared with prophylaxis. In a meta-analysis of six randomized clinical trials and four observational studies, episodic therapy was shown to be clinically inferior to prophylaxis with respect to degree of health/recovery, process of recovery, and sustainability of recovery.10,11

Economic impact

Costs associated with hemophilia A management in the United States can create financial toxicity among patients and families.7 The results of a meta-analysis of studies of healthcare resource utilization and economic costs of managing hemophilia A that were published between 2010 and 2022 (n = 40) found that the total annual healthcare cost per patient ranged from $213,874 to $869,940 (all 2021 US$). Results showed that the cost and intensity (dosing and frequency) of therapeutics comprised the majority of costs. Variation in drug-specific cost, population age, and intensity of prophylaxis contributed to the range of treatment costs.12

Inhibitor development is associated with additional cost burden. In an analysis of patient survey, clinical chart, and dispensing data for U.S. patients with hemophilia recruited between July 2005 and July 2007, the mean annual costs (direct and indirect) of patients with inhibitors (n = 10) were $1,153,594 higher than those for patients without inhibitors (n = 212) ($1,356,298 vs $202,704; inflated to 2023 US$).13,14

The importance of comprehensive care and individualized treatment

The WFH guidance for hemophilia A prophylaxis, endorsed by the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF), states that PwHA should be treated by a comprehensive, multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals (HCPs) with expertise in hemophilia; that this care be given through a designated center of excellence for hemophilia treatment; and that the relationship between should continue throughout the patient’s life.2

Treatment adherence can be a challenge to hemophilia management, particularly when PwHA transition to self-infusion in adolescence and when PwHA leave their parents and assume complete responsibility for treatment. Reduced adherence is associated with reduced treatment efficacy and can lead to bleeding and its sequalae. Patient preferences and experiences are vital to adherence and successful management.2

Dose and/or frequency should be individualized, monitored throughout life, and adjusted according to bleeding patterns, body weight, and other factors.2,3 Monitoring tools include self-reporting, pharmacy reporting, and the use of VERITAS-Pro, a validated questionnaire for patients or caregivers to assess FVIII prophylaxis adherence.3,15

For FVIII prophylaxis, dosing may be individualized based upon a patient’s pharmacokinetic profile.3 This may reduce inhibitor development, treatment nonadherence, morbidity, and overall treatment costs.2,16,17

The results of a meta-analysis of 73 studies of treatment adherence in patients with hemophilia showed that, within this population, the principal barrier to adherence was the perceived high burden of treatment, as treatment can require frequent, time-consuming, and seemingly complicated administration. A second barrier was a lack of perceived benefit to treatment. Because prophylaxis prevents bleeding and long-term complications, PwHA receiving prophylaxis may have no or low burden from bleeding and may question the need for ongoing treatment.2,18

Importance of consistent treatment

Partnership with a specialty pharmacy and appropriate utilization management strategies can help to improve outcomes and manage costs.19,20 However, for PwHA without inhibitors, switching treatments, such as from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab, is associated with increased treatment costs and negative or neutral clinical outcomes.5,21

Results of a study of IQVIA PharMetrics Plus administrative claims data (2015-2020) demonstrated that switching from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab was associated increased costs. Data indicated that the mean (SD) annual total cost of care (TCC) for 121 PwHA without inhibitors increased from $518,151 ($289,934) on FVIII to $652,679 ($340,126) on emicizumab (P < .0001; all 2020 US$).5

In an investigation of U.S. healthcare claims data (2015-2020) for 101 patients with hemophilia (A or B) without inhibitors, switching from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab was associated with a mean annual increase in TCC from $517,143 to $627,005 (P < .0001; all 2021 US$).21 Results of a U.S. all-payer claims database data (2014-2021) comparison demonstrated no significant differences in the mean annualized bleed rates for 131 PwHA without inhibitors after they switched from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab (P = .4456).22

Barriers to access

Lack of access to a comprehensive hemophilia care center and medical insurance restraints can act as barriers to treatment and negatively impact patient outcomes.2

An analysis of August 2019 data from the Tufts Medical Center Specialty Drug Evidence and Coverage Database and health plan websites revealed that coverage policies for hemophilia A varied across 17 commercial health plans. Among 296 commercial policies for 26 hemophilia A treatments, 57% covered a narrower patient population than indicated by the FDA label. Strict coverage included restrictions such as requiring patients with mild or moderate disease to have had two or more spontaneous joint bleeds before reimbursing for FVIII therapy. Of all policies with additional requirements, 30% required that patients fail other treatments before reimbursement.23

Novel therapeutic options

In June 2023, the FDA approved the first gene therapy for adults with severe hemophilia A, and anti-tissue factor pathway inhibition (anti-TFPI) and RNA interference (RNAi) therapies are being investigated for hemophilia A treatment.24,25 Compared with the current standard of treatment, these and other emerging therapies may help increase adherence and improve outcomes; however, long-term data will be needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of novel treatment options.

Conclusions

Approximately 12 in 100,000 males in the United States were affected with hemophilia A from 2012-2018.26 In an evolving treatment landscape, prophylaxis with a FVIII replacement or emicizumab and collaboration with a comprehensive care team remains the cornerstone of treatment for hemophilia A.2 A life-long, patient-centered approach that considers a patient’s bleeding patterns, body weight, pharmacokinetic profile, preferences, experiences, and values; emphasizes patient participation in decision-making; and values patient agreement with the course of treatment may reduce treatment nonadherence, inhibitor development, administration of excess dosage, morbidity, and overall treatment costs.2,3,17

References

- Day JR, Takemoto C, Sharathkumar A, et al. Associated comorbidities, healthcare utilization & mortality in hospitalized patients with haemophilia in the United States: Contemporary nationally representative estimates. Haemophilia. 2022;28(4):532-541. doi:10.1111/hae.14557

- Srivastava A, Santagostino E, Dougall A, et al. WFH guidelines for the management of hemophilia, 3rd edition. Haemophilia. 2020;26(suppl 6):1-158. doi:10.1111/hae.14046

- MASAC Document #267: MASAC recommendation concerning prophylaxis for hemophilia A and B with and without inhibitors. National Hemophilia Foundation. April 27, 2022. Accessed July 25, 2023.

https://www.hemophilia.org/sites/default/files/document/files/267_Prophylaxis.pdf - MASAC Document #276: MASAC recommendations concerning products licensed for the treatment of hemophilia and selected disorders of the coagulation system. National Hemophilia Foundation. May 2, 2023. Accessed July 25, 2023.

https://www.hemophilia.org/healthcare-professionals/guidelines-on-care/masac-documents/masac-document-276-masac-recommendations-concerning-products-licensed-for-the-treatment-of-hemophilia-and-selected-disorders-of-the-coagulation-system - Batt K, Schultz BG, Caicedo J, et al. A real-world study comparing pre-post billed annualized bleed rates and total cost of care among non-inhibitor patients with hemophilia A switching from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(10):1685-1693. doi:10.1080/03007995.2022.2105072

- Hoyer LW. Hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(1):38-47. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401063300108

- Agboola F, Rind DM, Walton SM, Herron-Smith S, Quach D, Pearson SD. The effectiveness and value of emicizumab and valoctocogene roxaparvovec for the management of hemophilia A without inhibitors. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(5):667-673. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2021.27.5.667

- Hemophilia A. National Hemophilia Foundation. Accessed July 25, 2023.

https://www.hemophilia.org/bleeding-disorders-a-z/types/hemophilia-a - Porada CD, Rodman C, Ignacio G, Atala A, Almeida-Porada G. Hemophilia A: an ideal disease to correct in utero. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:276. doi:10.3389/fphar.2014.00276

- Croteau SE, Cook K, Sheikh L, et al. Health care resource utilization and costs among adult patients with hemophilia A on factor VIII prophylaxis: an administrative claims analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(3):316-326. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2021.27.3.316

- Nugent D, O’Mahony B, Dolan G; International Haemophilia Access Strategy Council. Value of prophylaxis vs on-demand treatment: Application of a value framework in hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2018;24(5):755-765. doi:10.1111/hae.13589

- Chen Y, Cheng SJ, Thornhill T, Solari P, Sullivan SD. Health care costs and resource use of managing hemophilia A: A targeted literature review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2023;29(6):647-658. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2023.29.6.647

- Zhou ZY, Koerper MA, Johnson KA, et al. Burden of illness: direct and indirect costs among persons with hemophilia A in the United States. J Med Econ. 2015;18(6):457-465. doi:10.3111/13696998.2015.1016228

- CPI inflation calculator. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed July 25, 2023.

https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm - Duncan N, Kronenberger W, Roberson C, Shapiro A. VERITAS-Pro: a new measure of adherence to prophylactic regimens in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2010;16(2):247-255. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02129.x

- Lim MY. How do we optimally utilize factor concentrates in persons with hemophilia? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2021;2021(1):206-214. doi:10.1182/hematology.2021000310

- Hazendonk HCAM, van Moort I, Mathôt RAA, et al. Setting the stage for individualized therapy in hemophilia: What role can pharmacokinetics play? Blood Rev. 2018;32(4):265-271. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2018.01.001

- Mortensen GL, Strand AM, Almén L. Adherence to prophylactic haemophilic treatment in young patients transitioning to adult care: A qualitative review. Haemophilia. 2018;24(6):862-872. doi:10.1111/hae.13621

- Gilbert A, Tonkovic B. Case report of specialty pharmacy management of hemophilia. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(2):175-176. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.2.175

- Utilization Management. National Hemophilia Foundation. Accessed July 25, 2023.

https://www.hemophilia.org/advocacy/state-priorities/utilization-management - Escobar M, Agrawal N, Chatterjee S, et al. Impact of switching prophylaxis treatment from factor VIII to emicizumab in hemophilia A patients without inhibitors. J Med Econ. 2023;26(1):574-580. doi:10.1080/13696998.2023.2196922

- Escobar M, Bullano M, Mokdad AG, et al. A real-world evidence analysis of the impact of switching from factor VIII to emicizumab prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia A without inhibitors. Expert Rev Hematol. 2023;16(6):467-474. doi:10.1080/17474086.2023.2198207

- Margaretos NM, Patel AM, Panzer AD, Lai RC, Whiteley J, Chambers JD. Variation in access to hemophilia A treatments in the United States. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):1143-1148. doi:10.1080/13696998.2021.1982225

- Future therapies. National Hemophilia Foundation. Accessed July 25, 2023.

https://www.hemophilia.org/bleeding-disorders-a-z/treatment/future-therapies - FDA approves first gene therapy for adults with severe hemophilia A. Press release. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. June 29, 2023. Accessed July 25, 2023.

https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapy-adults-severe-hemophilia - Soucie JM, Miller CH, Dupervil B, Le B, Buckner TW. Occurrence rates of haemophilia among males in the United States based on surveillance conducted in specialized haemophilia treatment centres. Haemophilia. 2020;26(3):487-493. doi:10.1111/hae.13998

Newsletter

Get the latest industry news, event updates, and more from Managed healthcare Executive.