John Fetterman’s Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke: ‘I Almost Died’

Lack of an adherence may have been a factor. The Democratic Senate candidate stopped taking the medications he was prescribed after being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation in 2017.

This story was updated on Oct. 25

John Fetterman, the 53-year-old lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania and a candidate for the U.S. Senate, is among the lucky ones. He beat the odds.

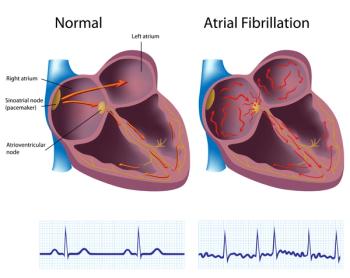

In 2017, he received a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation (AF), an irregular heart rhythm, and although his cardiologist got him started on a regimen of medication and exercise, Fetterman did not follow through.

Even for someone with AF, he was taking a big risk. The death rate for untreated AF at five years past diagnosis is

He was roughly 400 pounds (Fetterman has lost weight since) and 6 foot 8 inches tall. Taller people have larger atria and are more prone to AF. Diabetes, hyperthyroidism, use of tobacco and alcohol, high blood pressure, and advanced age are some other risk factors for this disease.

Fetterman suffered a stroke, one of the most serious consequences of AF, on May 13, 2022. “Like so many others, and so many men, in particular, I avoided going to the doctor, even though I knew I didn't feel well. As a result, I almost died,” Fetterman said in a statement.

The

In addition to AF, Fetterman has cardiomyopathy, according to a June 3

Although it is not spelled out, Chandra was likely referring to an

The Fetterman campaign subsequently released another letter about Fetterman's health from a different physician,

Chen describes Fetterman as recovering from well from his stroke and his lung exam was clear and his heart rate, regular. Fetterman continues to exhibit symptoms of an "auditory processing disorder," wrote Che. He says the disorder involves "missing" spoken words, which can seem like a hearing difficulty "but it is actually not processed properly." Chen said Fetterman is walking four to five miles a day and is taking "appropriate medications to optimize his heart condition.

Fetterman, concluded Chen, "is well and shows strong commitment to maintaining good fitness and health practice. He has no work restrictions and can work full duty in public office."

Fetterman is scheduled to debate Oz tonight at 8 pm. Eastern time. To help him with auditory processing, Fetterman is using a closed captioning device that renders spoken words into a written ones on screen. Attention on Fetterman's health has heightened in the days prior to the debate. Polls show that Fetterman's lead over Oz has narrowed, partly because voters are concerned about Fetterman's health.

Managed Healthcare Executive® spoke with Mayo Clinic specialist Peter Noseworthy, M.D., about untreated AF and why it's important to follow through on prescribed care. Noseworthy commented about AF in general and was not involved in Fetterman’s care. Noseworthy is a cardioelectrophysiologist and cardiologist in the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Typical treatment for AF involves drugs to slow the heart rate and maintain normal rhythm. Also important is minimizing the risk of stroke with blood thinners. Adherence to blood thinner medication, such as Coumadin (warfarin), “is notoriously poor,” Noseworthy said.

“Patients with AF often find that they are taking daily medications indefinitely, and these can often be multiple medications in combination. Adherence also means being cognizant of the fact that there may be triggers for AF and modifying lifestyle accordingly,” he said.

Although cost is sometimes a factor in patient adherence, Noseworthy said AF is so common that insurance coverage may be sufficient. “In general, the care for AF is covered as medically necessary care by (commercial) insurance and Medicare. But as with any healthcare in the U.S., treatment can become expensive, and depending on the way patients’ insurance plans are structured, there can be considerable out-of-pocket costs, especially if patients have been hospitalized or are undergoing procedures.”

Many patients opt for more costly treatments including direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), Noseworthy said. The DOACs include Eliquis (apixaban), Pradaxa (dabigatran) and Xarelto (rivaroxaban. AF patients are also prescribed drugs that address the underlying arrhythmia, including amiodarone, flecainide and propafenone.

Some AF patients are also treated with catheter ablation, Noseworthy explained. Catheter ablation involves ablating, or destroying, a small area of heart tissue that have been identified as being the source of the arrhythmia. The tissue is destroyed with an instrument that is threaded into the heart with a catheter.

For some patients, the treatment burden and lifestyle changes of atrial fibrillation may not be as drastic as they feared, said Noseworthy. Some people “live very well with AF and may have no symptoms whatsoever,” Noseworthy said. “Some patients are relatively debilitated by their AF, and they will require more aggressive treatment.”

Untreated AF can lead to heart failure or stroke. “Usually, we can get the symptoms under control. The goal is for them to return to normal life,” Noseworthy said.

Fetterman says he’s turned over a new leaf and is following doctor’s orders. In the June 3 statement, Chandra said “the prognosis I can give John’ heart is this: If he takes his medications, eats healthy and exercise, he’ll be fine.”

Chandra added that if Fetterman does what he has told him to do “he should be able to campaign and serve in the U.S. Senate without a problem.”

Newsletter

Get the latest industry news, event updates, and more from Managed healthcare Executive.