Research Suggests a New Way to Control Low Blood Sugar in Type 1 Diabetes

A study in mice finds that blocking somatostatin could restore the ability of the pancreas to release glucagon in the event of low blood sugar.

Inhibiting the hormone somatostatin could one day be a new treatment option to prevent low levels of blood glucose in patients with type 1 diabetes, according to results of recent study in mice

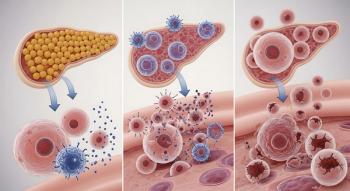

Somatostatin is a hormone in the pancreas that assists insulin and glucagon in regulating glucose levels. Insulin helps the body use glucose for energy. Glucagon is released when glucose levels become too low. Somatostatin is similar to a control switch for glucagon.

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not make insulin. But patients with type 1 diabetes also lack glucagon. Without glucagon, patients can experience dangerously low blood sugar levels, a condition that causes around 10% of all deaths in type 1 diabetes.

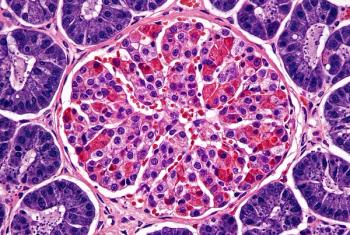

In this study, researchers from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden found that in mice with type 1 diabetes, blocking somatostatin could restore the ability of the pancreas to release glucagon in the event of low blood sugar. “This ‘electric brake’ is lost following autoimmune destruction of the β-cells, resulting in impaired counter-regulation,” the study authors wrote.

“The new findings highlight an important and previously unknown role of electrical signaling that occurs through open cell connections between beta cells and delta cells,” Anna Benrick, associate professor of Physiology at the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg and one of the authors, said in a

Benrick and her colleagues assessed non-obese mice with and without diabetes and compared glucagon secretion. They found that in non-diabetic mice, lowering glucose stimulated glucagon secretion but this process was reversed when glucose levels were raised. In mice with diabetes, the effect of low glucose on stimulating glucagon was weaker.

Researchers also found that the onset of type 1 diabetes led to a dramatic decrease in islet insulin but only marginally impacted glucagon and somatostatin. They suspected that excessive somatostatin secretion was what led to glucagon secretion in response to low glucose.

Researchers treated both non-diabetic and diabetic mice with the somatostatin receptor antagonist CYN154806. In the diabetic mice, somatostatin levels increased. Then they compared both the impact of CYN154806 on glucagon in both groups of mice with insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

They found that in non-diabetic mice, hypoglycemia increased glucagon by about 300%, but this effect was not seen in diabetic mice. In diabetic mice, researchers found that CYN154806 led to immune cells being able to penetrate the islet cells of the pancreas. This led to increased somatostatin secretion and glucagon secretion was inhibited.

Researchers then tested this in donated human islet cells. In healthy islets exposed to glucose, CYN154806 did not affect glucagon secretion. In islets from donors with type 1 diabetes, islet hormone contents were reduced and glucagon secretion was not increased when glucose was lowered.

Newsletter

Get the latest industry news, event updates, and more from Managed healthcare Executive.