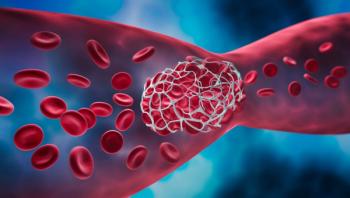

Gene Therapies for Hemophilia: Promising But There’s Room for Improvement, Say Reviewers

How long the gene therapies for hemophilia will keep factor levels high is unclear, said the authors of a review in the Annual Review of Medicine. Patients also need to be counseled that they can receive only one adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector in their lifetime.

The current crop of hemophilia A and B gene therapies approved or under development represents a genuinely new paradigm in care for this patient population, but these therapies are also quintessentially first-generation, and investigators see room for improvement.

“Despite repeated proof-of-concept success in current hemophilia gene therapy, stable, durable, [factor VIII (FVIII) or factor IX (FIX)] expression able to ameliorate bleeding in all patients is an unrealized hope,”

Samelson-Jones is an attending physician in the Division of Hematology at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and George is a hemophilia expert and directs the Clinical In Vivo Gene Therapy program at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Hemgenix (etranacogene dezaparvovec), which employs an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector to deliver a transgene to the liver to promote production of FIX, was approved in November 2022 for hemophilia B. It reduced the yearly bleeding rate by 65%, and 96% of patients no longer needed FIX replacement therapy two years after infusion.

However, the durability of the gene therapies designed to restore FVIII and FIX levels is unclear, and there is evidence that factor expression drops over time, Samelson-Jones and George wrote in their review.

Such has been the case with Roctavian (valoctocogene roxaparvovec), a trial drug under FDA review for hemophilia A, according to Samelson-Jones and George. Early trials demonstrated “continuously decreased FVIII levels out to six years” in participants, as well as a 40% loss of FVIII expression from year 1 to 2 in a phase 3 trial cohort, they wrote.

Gene therapy holds out the potential for lifetime normalization of FVIII and FIX levels following a one-time infusion, but many patients with hemophilia A and hemophilia B may not be eligible. “To date, only adult men with endogenous factor levels ≤ 2% and without advanced liver disease have received gene therapy,” noted Samelson-Jones and George.

Of particular concern is the role of AAV-neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) in modulating the effectiveness of gene therapy for hemophilia. The presence of a high degree of NAbs is correlated with gene therapy failure, and so prospective clinical trial participants with NAbs have been screened out. However, assays for NAbs are not fully reliable, and better tests are under development.

Anti-AAV NAbs can be acquired through natural infection, and environmental exposure accounts for an approximate 30% NAb seroprevalence.

Another potential problem is that NAb prevalence builds up significantly following gene therapy administration, which means that in the event of therapeutic failure, patients will never be eligible for another AAV-based gene therapy.

“The current lack of a proven strategy for vector re-administration is among the most salient considerations for clinicians and hemophilia patients when deciding on a gene therapy product,” wrote Samelson-Jones and George.

“Patients should be counseled so that they are fully aware that the current state of clinical development only permits one lifetime systemic AAV vector administration,” they said.

For payers, the prospect of a multimillion-dollar tab for a failed gene therapy, which would then be followed by additional costs for a lifetime’s return to standard-of-care, could be sobering. In hemophilia A and hemophilia B, the standard of care is infusion of FVIII and FIX concentrate up to several times a week to achieve hemostasis.

After being accepted for clinical trial participation and being administered gene therapy, some patients were found to have AAV NAbs, and yet the gene therapy for them was still effective.

A larger gene therapy “vector” dose may be of significance in whether AAV Nab levels are treatable or refractory, observed Samelson-Jones and George. “Indeed, [Hemgenix] is administered at a 40-fold higher vector dose” than other AAV vectors studied. However, there is evidence to suggest that dose-limiting toxicities could be an issue with hemophilia gene therapies.

“Work is ongoing to develop methodologies to eradicate or avoid preexisting antibodies as well as prevent formation after vector administration,” wrote Samelson-Jones and George.

Newsletter

Get the latest industry news, event updates, and more from Managed healthcare Executive.