Assist populations with obesity prevention

Physicians and local communities assist in obesity prevention.

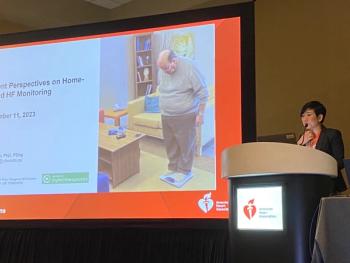

Experts generally agree that more than 60% of Americans are overweight or obese. Everyone knows that obesity can lead to diabetes, heart disease, stroke, kidney failure and certain types of cancer, and overweight and obesity have become the second leading cause of preventable death in the United States.

Obesity alone accounts for $147 billion to $210 billion in costs each year, according to the Trust for America’s Health. It is also the cause of 200,000 deaths annually and is more prevalent than tobacco use.

Obesity affects employers through absenteeism, presenteeism and higher healthcare costs. Families might be affected by reduced earnings when parents miss work and by increased care costs. Individuals often suffer a reduced quality of life and even discrimination in hiring practices or social settings. Health plans also see the financial effects of member obesity and overweight in higher claims.

With such high costs at stake, one would think industry organizations would have found reasonable solutions by now-and some have. For example, Kaiser Permanente’s (KP) Community Health Initiatives aim to increase healthy eating and active living through environmental and policy change, including work in neighborhoods, schools, workplaces and the health sector.

Kaiser Permanente’s exercise vital-sign initiative records members’ physical activity in their electronic health records during routine outpatient visits. Visits also include personal conversations to find unique ways to encourage members to engage in more activity, such as walking a dog or planting a garden. The organization also produced a toolkit that helps clinicians learn how to initiate such conversations.

“This creates a better relationship because now we know that person likes to garden or has a pet, so it’s a real discussion about that person’s quality of life,” says Trina Histon, senior manager of clinical pathway improvement and director of obesity prevention, treatment and behavior change at KP.

KP also offers the Amazing Food Detective online game to help educate children and works to improve food choices and students’ physical activity at schools. Results reported in the American Journal of Health Promotion showed children’s physical activity could be improved as a result of health interventions, such as increasing active minutes during school physical-education classes, increasing minutes of activity in after-school programs, and increasing walking and biking to school.

Overall, Histon says that KP tries new things and “figures out what works for folks” with an evidence base. One example of evidence-based care is a new emphasis on telephonic coaching for weight loss.

“Folks like face-to-face classes, but the literature says the more contact points there are, the more likely people are to keep off the weight,” she says. “But people drop off. So, we’ve been playing around with different modalities. One is to not only come and sit in a class but to get tailored one-on-one phone coaching.”

Look outside your four walls

Histon offers some advice from Kaiser Permanente’s experience. First, look beyond your business model.

“We didn’t have to open farmer’s markets or safe routes to school, but we realized that creating good health is complex and has multiple components,” she says.

Second, she says to remember that health plans attempting to reduce obesity rates for members or populations don’t have to do it alone. Find like-minded partners in the community. Show up at housing and zoning meetings to discuss the need for green spaces, for example. Or have clinical staff go to school board meetings and encourage wellness policies, she says.

Rebecca Puhl, director of research and weight bias initiatives at the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity at Yale University, endorses the idea of new approaches. A single solution won’t create full impact.

“Obesity is a condition that has resulted from a complex interaction of genetic, biological, environmental, societal and individual factors,” she says. “We have to address all of those things if we want to effectively address obesity.”

She says, for example, schools and workplaces are areas to target. Administrators are seeing progress more quickly in schools than in other settings, she says, noting the rise in school nutrition efforts. Schools are beginning to remove vending machines, and larger policies are improving nutritional requirements for food sold in schools, such as in cafeterias.

Puhl says workplaces are also implementing new programs. She encourages employers to reward employees for steps such as taking health evaluations, meeting with dieticians, measuring their blood pressure and earning health rewards for gym memberships.

Dieticians offer support

Anne Wolf, a dietician with Anne Wolf & Associates in Charlottesville, Va., has had success with a model called Improving Control with Activity and Nutrition, or ICAN, which was presented in the journal Diabetes Care in 2004. Case management in the model includes group education, support and referral by registered dietitians.

Wolf works for employers to keep healthcare costs down. Registered dieticians and nurses oversee the program once an employee has initially met with a primary care physician. In addition, much of the follow up is conducted by phone or online. Average weight loss is 16 to 18 pounds after six months, and 98% of participants usually complete the program, she says.

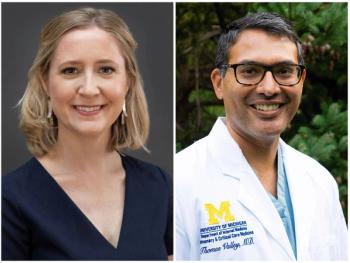

Kurtis Elward, MD, medical director for Coventry Health Care, has worked with Wolf on several programs, including one with Albemarle County in Virginia. He says that the first step is to identify the employees who could most benefit and to give them time to participate. Another key, he says, is reimbursement for the care-management services.

Andrew Rife is a specialist in naturopathic medicine for Puget Sound Family Health in Tacoma, Wash. He developed “Weigh to Live,” a 12-week group educational program focused on nutrition that first targets blood sugar regulation, then an elimination diet and finally portion control. The program tracks improvements in bio-markers such as cholesterol, triglycerides, inflammation, blood sugar and blood pressure.

“It’s designed to discover foods that work well for your body and, more importantly, those that don’t,” Rife says. “It helps people learn the correct pattern for eating to maximize weight loss.”

Rife’s co-investigator is Jill Nealy-Moore, professor of Psychology at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma. Nealy-Moore added a component to address the cognitive and emotional issues related to diet.

“This is consistent with research saying that if you address nutrition without emotional response to eating, if you just give people directives, the changes don’t tend to last. We try to help people understand their relationship with food,” she says.

Regardless of the approach, experts agree that prevention and targeting members just as they start to put on weight might have the best results.

“This is where the role of the physician can be very important,” says Daniel Callahan, senior research scholar and president emeritus at the Hastings Center. “Physicians, in most studies, aren’t good at raising this topic. Some patients are sensitive about it.”

Newsletter

Get the latest industry news, event updates, and more from Managed healthcare Executive.